Sarita was nine months pregnant when she suddenly began to discharge an abnormally large amount of water. She was expecting to give birth at home like most of the women in her small village of Ratanpur, Bihar. Although government hospitals are available, the villagers prefer to give birth at home according to their own traditions.

Urmila is Amrita SeRVe’s health worker and village coordinator in the area. Hearing about Sarita’s condition, she rushed to her side and convinced Sarita that they go to the nearby hospital. The nurse there advised that Sarita be admitted, since she was about to give birth at any time. Sarita agreed but soon after Urmila left her bedside, she ran away.

“What kind of people are you bringing here?” the nurse confronted Urmila the next day. “See how she suddenly left?”

Urmila found Sarita doubled over in pain at her home and convinced her, yet again, to get to the hospital. But upon return there, the hospital refused admission. “We cannot help her now,” the doctor said. “Her running away has made her condition much worse. The baby is probably dead. We cannot handle this kind of situation.”

The next decision Urmila made was to take Sarita to another government hospital in the nearby city of Ara. There they operated, removing the dead baby and saving Sarita’s life.

Grim situations like this do not deter Urmila from her work in Ratanpur, where most of the people are from a community named the Musahars. The living conditions of the Musahars are, by far, deplorable. As one of the poorest communities in all of India, they were considered outcaste before the country’s independence from British Rule. Under the new constitution, the Central Government granted them scheduled caste status so they could access social service support.

But still more than 70 years later, the Musahars suffer in abject poverty, enduring malnutrition alongside high maternal and infant mortality rates. As part of that formula, literacy rates are exceedingly low. Only six percent of the men and two percent of the women can read or write. In addition, the people are often not educated in basic hygiene and sanitation practices.

Not being landowners, they take jobs as laborers for Rs 200-250 ($3 US) per day. The tasks are mostly in areas such as agriculture, block making or truck loading and are only available on a seasonal basis. Much of the year is spent unemployed.

Amrita SeRVe’s goal in Ratanpur is to help the Musahars establish themselves so they can live a dignified life. This means not only providing basic needs, but also showing them that they too are people who deserve respect from and caring by others. Having grown up under the label of a poor and backward class, many of them do not even believe in their own self-worth.

To begin a change in both external and internal perceptions, Urmila has started with primary health as her key focus. Without good health, not much else can be achieved. She holds regular awareness sessions for women and children and also visits homes to check on the health status of families. When she discovers serious conditions, she personally takes the patients to the area’s Primary Health Center (PHC) or, in urgent cases, the nearest hospital.

Urmila is from the nearby village of Hadiyabad, but regardless, she finds it difficult to convince the people of Ratanpur to adapt changes that will improve their lives. After historically living as a marginal group, they have a lack of trust in outsiders – especially government infrastructure. It even took Urmila herself a long time to gain the villagers’ support for her health work.

“They don’t just want to change because someone’s coming to give awareness,” Urmila explains. “I’m from another village – an outsider – so why should they listen to me?”

Eventually, though, Urmila was able to prove she truly was there to help the people in Ratanpur gain access to better lives. She started by bathing the children, who were covered in dust and dirt, every two weeks. As people began to understand and accept her, she was able to bathe the kids once a week.

Villagers next became open to vaccination sessions for illnesses such as polio and measles that Urmila coordinated with the area’s government health workers. She was also able to bring some awareness to pregnant women and new mothers who needed to boost their nutritional intake by eating more greens and taking iron tablets.

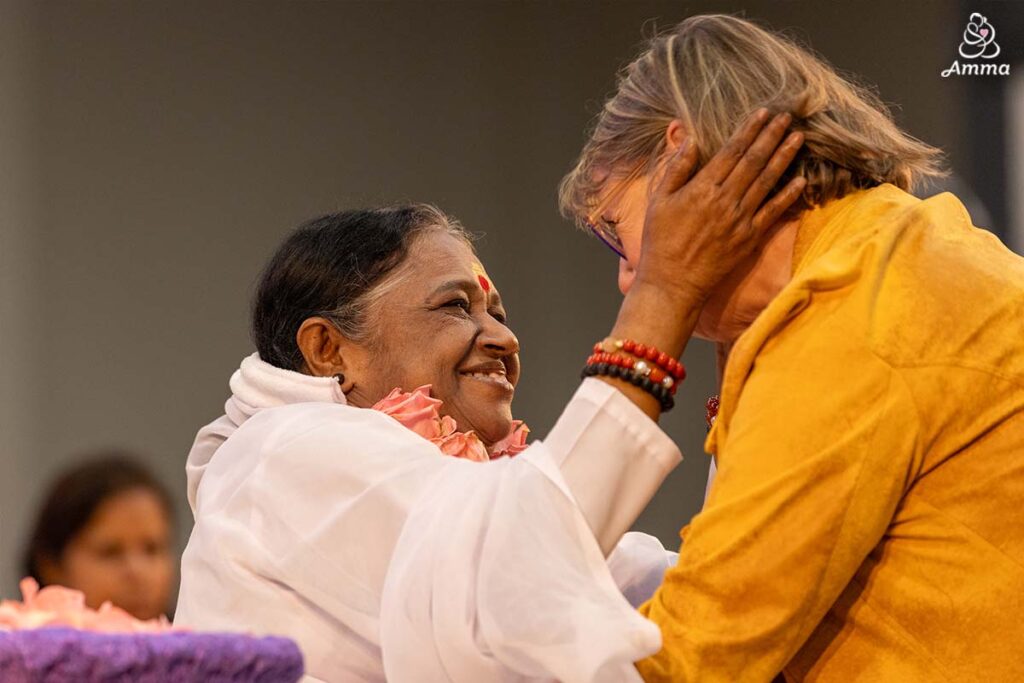

Urmila’s mission to undertake this work in Ratanpur began in January 2016 when she was offered the opportunity to travel to Amritapuri and meet Amma for the first time. There, she was also introduced to the head of Amrita SeRVe who asked if she would like to get training as a health worker. Feeling the definite call in her heart, she quickly answered, “Yes.” Urmila began her job with Amrita SeRVe that following March.

Despite the trying circumstances that only lead to small steps of progress, Urmila remains dedicated. A recent testimony to this new foundation of trust between Urmila and the villagers is the story of Nita Devi. Four months into her pregnancy, she had severe swelling in her feet.

After the necessary tests were complete at the PHC, Urmila told Nita Devi that if she didn’t take care of herself and eat properly, a more serious condition could result. Nita Devi began following Urmila’s instructions, even asking for the next step in her prenatal care and allowing Urmila to take her for antenatal check-ups at the PHC. Six months later, Nita Devi gave birth to a healthy baby girl.

Urmila has not yet won the trust of every family in Ratanpur, as many still refuse her counsel to access the public health care system. That being said, she is determined to keep reaching out. Urmila’s focus is soundly based on the pathway to a better future for the Musahars of Ratanpur, one human being at a time.